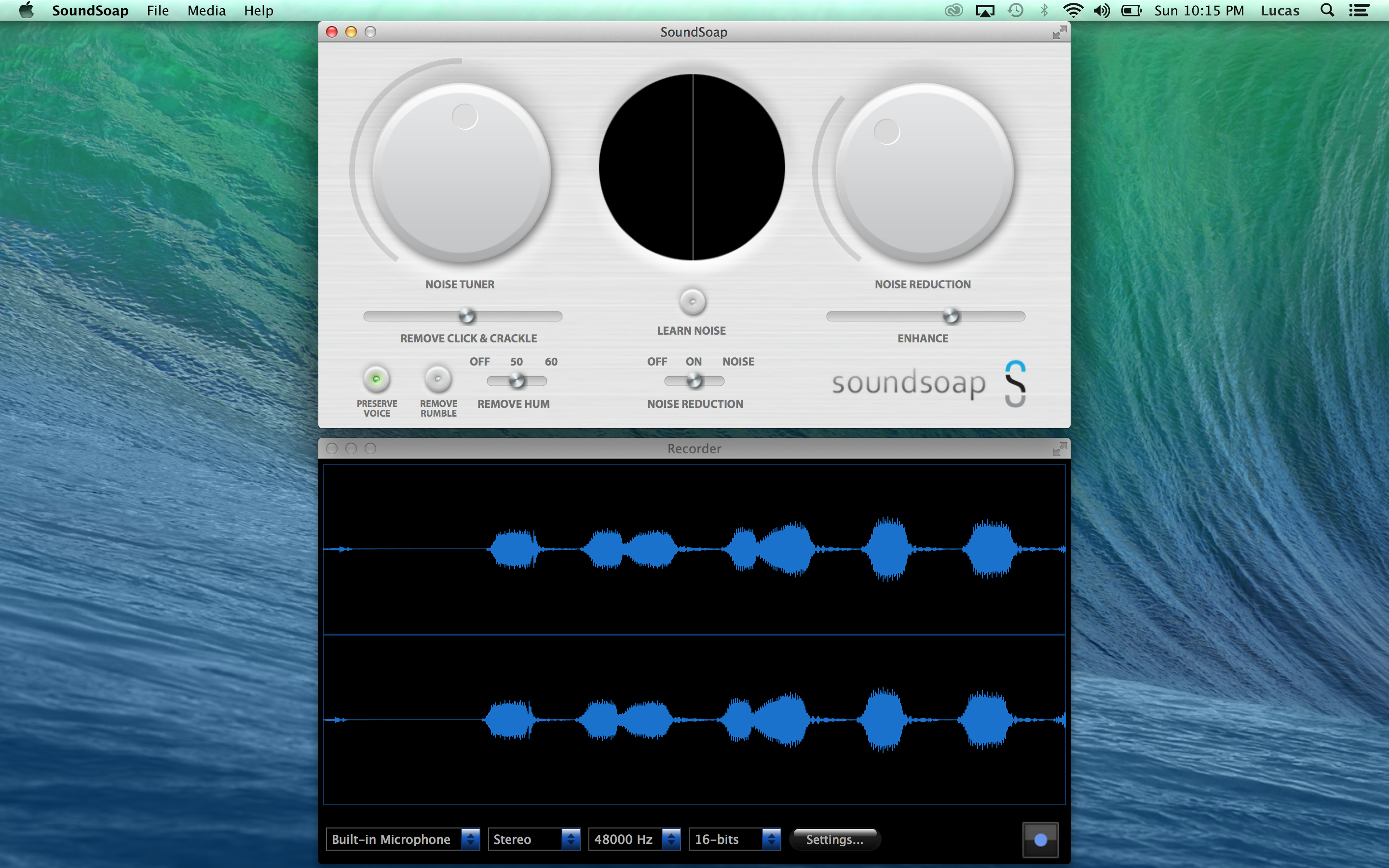

These types of processors demand a different approach. By simply turning up that single fader as far as possible before artifacting began to set in, there were many cases in which when the NS-1 allowed me to obtain results that matched or surpassed its big brothers, and in significantly less time.įar more popular in music and restoration are plugins in our second category: Graphical noise-reducers such iZotope RX2, Wave Arts’ MR Noise, the Sonnox Oxford DeNoiser, and Z-Noiseby Waves that rely on “noise profiles.” They take after an earlier generation of tools popularized by Sonic Solutions, Sony, Digidesign, and BIAS, the now-defunct developers of SoundSoap. Surprisingly, even once the learning curve is overcome, one of the most effective noise reducers from Waves turns out to be the NS-1 from their “Single Knob” series, street price: only $99. In practice, they might not be quite as effective as a Cedar system, but they carry 1/10th the price tag, and the WNS’ welcome “suggest” function can be a great shortcut and learning aid for new users.

Waves has recently taken a step into this world, releasing the WNS and the W43, their own versions of these no fader-based no-latency noise reducers.

Soundness soundsoap series#

Still, the Cedar DNS series remains among the most popular noise reducers in broadcast and post circles thanks to its super-low latency, hardware integration, and a proven record for cleaning up dialog tracks in real-time. They rely on the ear more than the eye, inviting the user to manually set a threshold for each band individually, until maximum noise reduction is achieved without compromising the sound of the original signal in that frequency range.

The first category of fader-based noise-reducers, such as the Cedar Audio DNS One or the Waves WNS and W43, pay homage to the old-school processors like the Cat43. There are two major types of broadband de-noisers on the market today: Those with fader-based interfaces reminiscent of the Cat43, and those with graphical, noise-sampling interfaces that are only practical within the DAW domain. Where the earliest analog noise reducers made do with a few bands of frequency-sensitive downward expansion, today’s digital processors are often comprised of hundreds of bands working in concert. It was a fairly complex circuit for its era, but devices like this one made reducing significant ambient and broadband noise a real possibility for the first time.Īlthough today’s best noise reduction tools are far more powerful, they rely on the same principles that let the Cat43 do its job. It was an analog device that combined several frequency-selective gates, one each for bass, low-mids, high-mids and treble. There are a series of tradeoffs inherent in any of these primitive solutions: Filters effect tone and rarely stand up to broadband noise, while conventional expander/gates are only really effective if the noise level is quiet enough to begin with, so that it’s masked by the desired signal once the gate opens.īut the tools of the trade took a huge step forward when Dolby released the Cat43. Basic expansion or gating could even push low-level noise down further, making the noise floor seem to disappear.

A high-pass filter could allow you to fight rumble and plosives, a low-pass might help tame hiss, and a series of notch filters could help with 60-cycle hum. Not long ago, if you wanted to clean up noise your primary option would have been to employ simple filters, expanders and noise gates. We put a few of the most popular of these plugins through their paces to find out how they stack up. Some of them, like Sony’s Spectral Layers, will even let you “Unbake The Cake,” by removing not just broadband noise and ambience, but individual sounds and instruments from within a single track. On today’s market, you’ll find a few of the most powerful sonic-scrubbers ever devised, with prices that range from $100, right on up to near $10,000. Fortunately, the tools have been keeping up with the increased demand.

Soundness soundsoap zip#

Music is increasingly tracked in home studios where refrigerators hum, amps buzz and cars zip by outside windows a growing amount of video is shot remotely on makeshift sets where booms and lavs won’t go, camera preamps hiss, and ambient noise can begin to overwhelm.Īll this conspires to make audio cleanup a recurring task for engineers who rarely had to deal with these jobs in the past. In a controlled environment, like a recording studio or a film set, you’re blessed with a quiet space, clean power and revealing monitors, so that isn’t too difficult to do.īut these days, for better and for worse, more audio is being recorded in compromised environments than ever before, and at every level in the industry.

The best way to deal with a troublesome noise is to avoid recording it in the first place.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)